As educators we need to set the tone in our classrooms—we need to serve as the thermostat, not the thermometer. We know that if we ride the waves of emotion our students bring into our classroom, we’re likely to make the highs higher and the lows lower, creating an emotional rollercoaster ride for all.

But being the thermostat isn’t easy, especially when we get triggered ourselves, whether by a group of rowdy students who refuse to settle down, by one particularly disrespectful student who knows exactly what buttons to push, or by a colleague we think is being unreasonable.

It’s in situations like these that it is especially important to have a practice that can help us to maintain our calm. We want to be able to counteract the body’s natural response to fight, flee or freeze, when the reptilian part of our brain believes our survival is at stake. There are a number of strategies we can use to reclaim control, regulate our emotions, and make fitting decisions in the moment.

A good first step is deep breathing. Taking some deep abdominal breaths can help our brain to calm down and relax. As the supply of oxygen to the brain is increased, the parasympathetic nervous system returns the body to a state of calm, by bringing our blood pressure and heart rate back down.

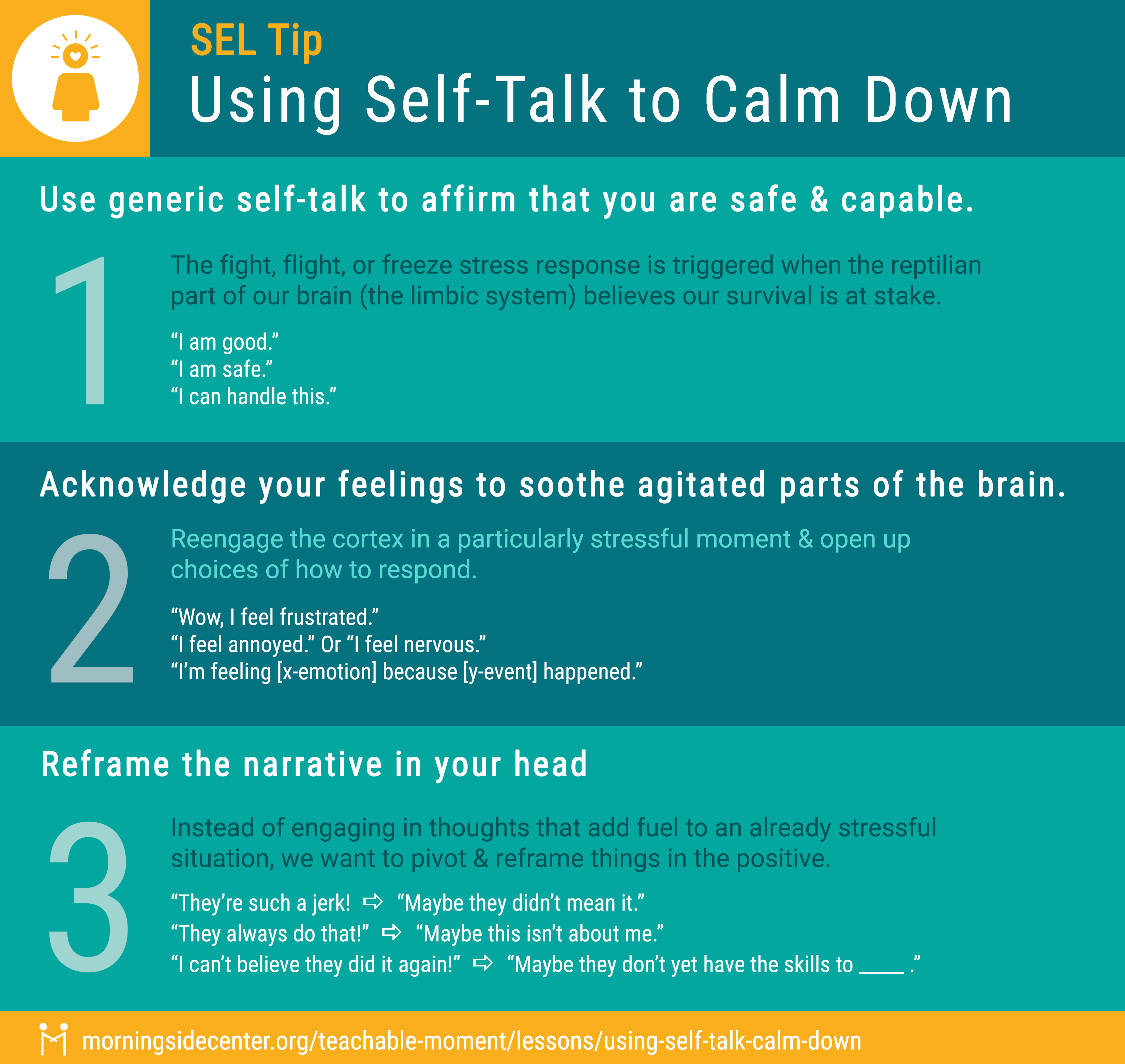

A second, complementary strategy is self-talk, which enables us to soothe and calm the anxious parts of the brain. This requires us, first, to recognize that we have a voice inside our heads that can either calm us down, or add fuel to a situation, further escalating our emotions. Once we’re aware of this internal voice, we can direct it in some or all of the following ways:

1. Generic self-talk. The fight, flight, or freeze stress response is triggered when the reptilian part of our brain (the limbic system) believes our survival is at stake. Affirming that we are safe and that we are capable of handling the situation can help counteract the stress response and reengage cortex. We might tell ourselves:

- “I am good.”

- “I am safe.”

- “I've got this.”

2. Acknowledging our feelings. We know that acknowledging feelings helps soothe the agitated parts of the brain. Neuropsychologist Dan Siegel calls this “naming to tame it.” Acknowledging our feelings can reengage the cortex in a particularly stressful moment and open up choices of how to respond after a situation in which we “flipped our lid.” Self-talk examples are:

- “Wow, I feel really anxious.”

- “I feel annoyed” or “I feel frustrated.”

- “I’m feeling [x-emotion] because [y-event] happened.”

3. Reframing the narrative in our head. Instead of engaging in thoughts that add fuel to an already stressful situation, we want to pivot away from negative thoughts and instead reframe things in the positive. For instance, we might add fuel to a situation by thinking:

- “He’s such a jerk!"

- “They always do that!”

- “I can’t believe they did it again!”

Instead, we might move to calming thoughts such as:

- “Maybe they didn’t mean it.”

- “This probably isn’t about me, they seem to be having a bad day."

- “They don’t appear to have the skills yet, to ________________ .”

By maintaining our calm in stressful, triggering situations, we educators can set a positive tone in the classroom, send a comforting message to our students, and maintain full access to the problem-solving part of our brain so that we can make appropriate choices in the moment.