To the teacher:

For three days in early January 2015, two al-Qaeda affiliated brothers and an associate shook France, Europe and much of the rest of the world. The two brothers forced their way into the offices of France’s satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, where they targeted and killed 10 people at a lunch-time editorial meeting. They also shot and killed the editor’s bodyguard and executed a police officer, Ahmed Merabet, as he tried to stop the terrorists.

The next day, while the brothers, now identified as Cherif Kouachi and Said Kouachi, were on the run, the associate, later identified as Amedy Coulibaly, is said to have killed another police officer in the southern Paris suburb of Montrouge. A manhunt across France, deploying 80,000 police, ended two days later on January 9 in a blaze of gunfire and explosions. The Kouachi brothers, holed up in a printing plant north of Paris with a hostage, were shot and killed. Coulibaly had taken hostages at a kosher supermarket on the eastern edge of the city. Four of the hostages and Coulibaly were killed.

Witnesses at the Charlie Hebdo offices heard the gunmen shout "We have avenged the Prophet Muhammad" and "Allahu Akbar," which is Arabic for "God is great." The apparent Islamist militant attack was in response to the newspaper’s publishing of satirical cartoons of the prophet Muhammad. In an interview with journalists hours before he was killed, Cherif Kouachi claimed to have been sent by Al-Qaeda in Yemen as a defender of the prophet. Amedy Coulibaly, also speaking with a journalist the day he was killed, claimed to have committed his acts to defend oppressed Muslims.

On January 11, over a million people took part in a "unity march" in Paris to protest the violence. It was the largest demonstration in French history. Two million more marched in cities across France.

A note on the use of the word "Islamist"

Note that in describing the Kouachi brothers and Coulibaly, we use the word "Islamist" - not "Islamic" or "Muslim." Islamism, also known as political Islam, refers to an ideology that considers Islam not as a religion but as a political system that expects all Muslims to turn to a militant form of their religion and to unite politically. Muslims who do not espouse this view are considered to be infidels by Islamists as much as non-Muslims are.

Some people are quick to generalize and incorrectly equate Muslims with Islamists, a tiny minority of extremists who use Islam to promote their views - much as a handful of extremists use other religions like Christianity, Judaism or Hinduism to propagate their political agenda, at times using violence to attain their goals. It's important to foster better understanding of these distinctions and to be especially sensitive to this issue if there are Muslim students in your classroom.

To distinguish the Kouachi brothers and Coulibaly from other Muslims in France and beyond, you may point to Ahmed Merabet, the French Muslim police officer who was executed by the brothers as he tried to stop them from fleeing the crime scene at Charlie Hebdo, or Lassana Bathily, the Malian Muslim employee of the Kosher supermarket. Bathily ushered more than a dozen customers into the supermarket’s cold storage away from the heavily armed Amedy Coulibaly, before going outside to help with the police rescue of the hostages.

Gathering:

Charlie Hebdo Web

Ask students what associations they have with the name "Charlie Hebdo." Consider charting their associations graphically as a web to create a visual representation. Making a web often stimulates creative thinking. To make one, write a core phrase, in this case "Charlie Hebdo," in the center of the board and circle it. Student associations with the core phrase are written so that they radiate out from the center. Related ideas can be grouped.

Encourage associations while energy is high. Ask open-ended questions to stimulate responses from groups that are struggling to come up with associations. As energy tapers off, ask students to read what's on the web and ask some or all of the following debrief questions:

- What do you notice about the web?

- Are there generalizations we can make about what's on the web? Explain.

- Is there anything on the web that is surprising to you? Explain.

Ask a few volunteers to share what they know about the events that took place at the Charlie Hebdo offices in early January and possible connected events in Paris that week.

Add to what your students share by touching on what is written in the "to the teacher" section at the start of this lesson plan.

Check Agenda and Objectives

Explain that in today’s lesson you’ll be exploring a range of responses to the Paris attacks (and their aftermath) by looking at tweets from a series of hashtags that have trended since early January.

All tweets used in today’s lesson express solidarity in some way. Expressions of solidarity can spring from a shared need for healing. They can help a community come together after situations of crisis, promoting the kind of unity called for in the march in Paris after the attacks.

Students will be asked to think critically about the impact of these tweets, intended or otherwise.

Exploring Different Tweets in Response to the Paris Attacks

Elicit and explain that people around the world used social media to respond to the attack on Charlie Hebdo using the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie, which translates to #IamCharlie, in what was widely seen as a show of solidarity with those mourning in Paris and a support of free speech. Other hashtags appeared soon after with a different take on solidarity in the aftermath of the events. Below are a range of tweets pulled from different Twitter handles related to the Paris attacks for you and your students to explore.

Hashtag 1: #JeSuisCharlie (#IAmCharlie)

The #JeSuisCharlie hashtag trended overwhelmingly on twitter in various different languages in the days following the attacks. The slogan was also chanted at the unity rally in Paris that brought together a diverse crowd of over one million the Sunday after the attacks. The slogan is meant to express solidarity with the victims of the attacks and with those mourning in its aftermath, as well as support for free speech.

Je Suis Charlie has been seen and heard across France and even made it on to the Hollywood red carpet and stage during the Golden Globe Awards as American actors pledged their solidarity with those in Paris. In his acceptance speech for the Cecil B. DeMille Award, George Clooney was quoted as saying:

"Millions of people - not just in Paris but around the world, Christians and Jews and Muslims, leaders of countries all over the world - they didn’t march in protest, they marched in support of the idea that we will not walk in fear. We won’t do it. So Je Suis Charlie."

Using the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie, many on Twitter also replaced their profile photo with a white-on-black image of the phrase:

Ask students:

- Are you familiar with the image and the phrase?

- Do you know people who used it (or the translation "I am Charlie")? If so, do you know why?

Project or hand out a printout of the following tweet for students to study before asking the questions below it:

Text of the tweet:

"Any act of violence against journalists & satirists will only serve to strengthen the resolve of both #JeSuisCharlie"

Ask students:

- What are your thoughts are about the show of solidarity in this tweet?

- What might the tweet be trying to convey?

- Who is the tweet in solidarity with?

- What is it intended to convey about freedom of expression?

- Who might feel left out or offended by the tweet? Why?

Project or hand out a printout of the following tweet for students to study before asking the questions below it:

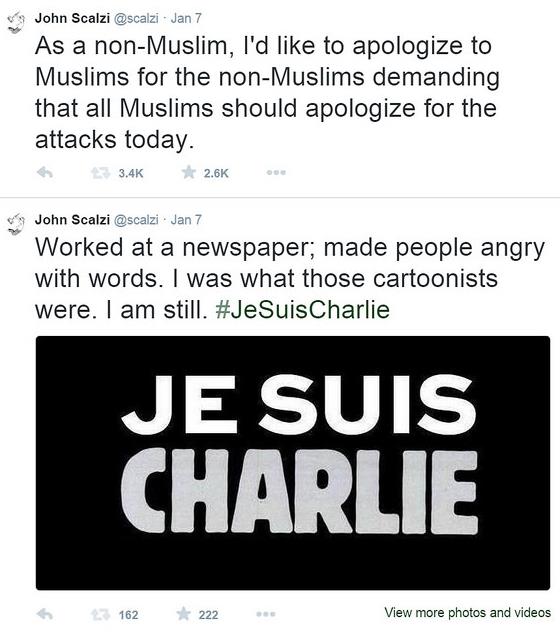

Text of the two tweets, both by John Scalzi:

"As a non-Muslim, I'd like to apologize to Muslims for the non-Muslims demanding that all Muslims should apologize for the attacks today."

"Worked at a newspaper; made people angry with words. I was what those cartoonists were. I am still. #JeSuisCharlie"

Ask students:

- What are your thoughts are about the show of solidarity in the top tweet?

- What is the tweet trying to convey?

- Who is the tweet in solidarity with?

- What does that second tweet try to convey?

- Who is the tweet in solidarity with?

- What does it say about freedom of expression?

- What does the combination of the two tweets convey?

- Who might feel left out or offended by these tweets? Why?

The #JeSuisCharlie tweets dwarf all other Charlie Hebdo trends but other reactions have appeared online since the attacks as well. Days after the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie started trending on Twitter, other tweets and hashtags appeared that may help us contemplate a more complex response to the attacks on Charlie Hebdo and the kosher supermarket.

Hashtag 2: #JeNeSuisPasCharlie (#IAmNotCharlie)

Project or hand out a printout of the following tweet for students to study before asking the questions below it:

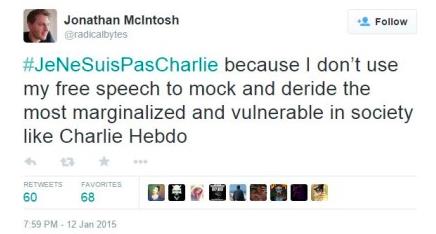

Text of the tweet:

"#JeNeSuisPasCharlie [I am not Charlie] because I don't use my free speech to mock and deride the most marginalized and vulnerable in society like Charlie Hebdo"

Ask students:

- What are your thoughts are about this show of solidarity in this tweet?

- What is the tweet trying to convey?

- Who is the tweet in solidarity with?

- What does the tweet say about free speech?

- Who might feel left out or offended by this tweet? Why?

This tweet (and others than follow) may raise new questions about the content of Charlie Hebdo. What do students know about the content of Charlie Hebdo? What do they know about it "mocking and deriding" the most vulnerable in society? If questions like these come up, record them for future exploration.

Hashtag 3: #JeSuisAhmed

Project or hand out a printout of the following tweet for students to study before asking the questions below it:

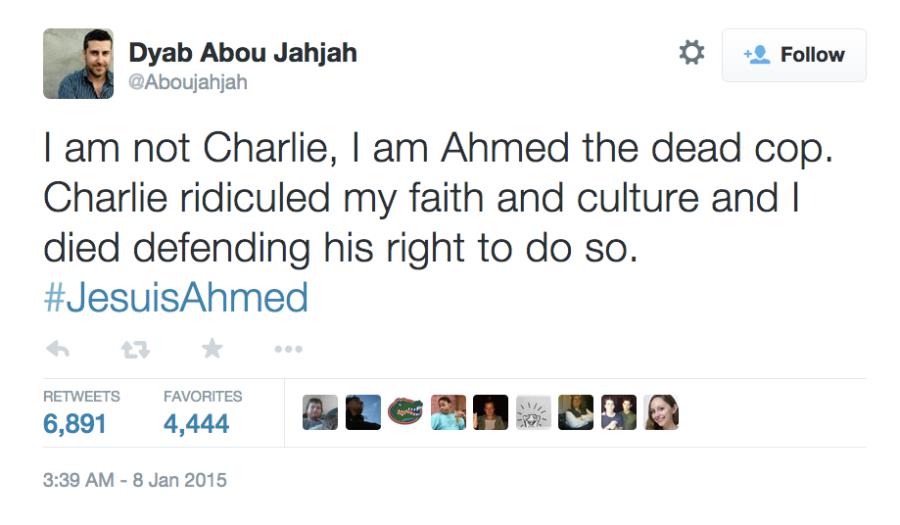

Text of the tweet:

"I am not Charlie, I am Ahmed the dead cop. Charlie ridiculed my faith and culture and I died defending his right to do so. #JesuisAhmed"

Ask students:

- What are your thoughts are about this show of solidarity in this tweet?

- What is the tweet trying to convey?

- Who is the tweet in solidarity with?

- What does the tweet say about free speech?

- Who might feel left out or offended by the tweet? Why?

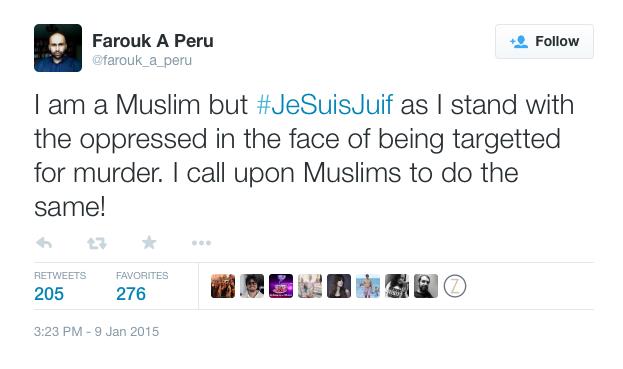

Hashtag 4: #JeSuisJuif (#IamJewish)

Project or hand out a print up of the following tweet for students to study before asking the questions below it:

Text of the tweet:

"I am a Muslim but #JeSuisJuif [I am Jewish] as I stand with the oppressed in the face of being targeted for murder. I call upon Muslims to do the same!"

Ask students:

- What are your thoughts are about this show of solidarity in this tweet?

- What is the tweet trying to convey?

- Who is the tweet in solidarity with?

- What does the tweet say about freedom of religion?

- Who might feel left out or offended by the tweet? Why?

Creating Your Own Tweets

In small groups ask students to come up with a tweet based on today’s lesson that they might want to share online. Ask a few groups to share out their tweets and invite the rest of the group to provide feedback by asking them to discuss:

- What do you like about this tweet? Explain.

- What is the tweet trying to convey?

- Is the tweet in solidarity with anyone? If so, whom?

- Does the tweet say anything about freedom of expression and/or freedom of religion? What?

- Who might feel left out or offended by the tweet?

- Is there anything you’d suggest the group change about this tweet? If so what? Why?

Closing

Ask students to share one thing they learned today.

Homework and follow-up discussion

Return to or create a list of questions raised by today’s discussion. They might include:

- What does Charlie Hebdo publish?

- What is the mission of this publication?

- Who does it target with its satire?

Once students have researched these questions, discuss the information they have collected. Discussion might touch on questions such as:

- What is your opinion about the material that Charlie Hebdo publishes, and their stated motive, as you understand it?

- What do you think is valuable - or at least worth defending - about Charlie Hebdo?

- What is troubling or might be offensive about Charlie Hebdo?

- What is the value of satire in general?

- What do you think about the following statement: "Good satire makes the powerful uncomfortable, while comforting the marginalized." How does it relate to the content of Charlie Hebdo?

- With rights come responsibilities. What responsibilities do you think should accompany the right of free speech?

- How can we respond to statements or images that we find offensive in ways that honor the right to free speech?