To The Teacher

A report published by Oxfam in 2019 showed that the richest 26 individuals in the world own as much wealth as the bottom half of humanity, some 3.8 billion people. This report is just the latest piece of evidence that wealth disparity across the world continues to grow.

A number of high-profile politicians have proposed that the wealthy should pay more in taxes. In early 2019, newly elected Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez caused a minor uproar in Washington, DC by proposing to nearly double the income tax rate on top earners: Under her plan, the rich would pay a tax rate of 70 percent on income over $10 million. Subsequently, Senator Elizabeth Warren, who is running for president, proposed taxing not just large incomes, but also accumulated wealth. Advocates argue that the increase in revenue from these measures would make it easier to fund popular ideas such as Medicare for All and free college tuition. And they contend that taxing the wealth of the top 1 percent could reduce inequality and help level the playing field of our democracy. Opponents argue that these high tax rates would stifle economic activity.

This lesson consists of two readings. The first examines the historical precedent for increased taxes on the wealthy, criticism of the idea, as well as some of the potential economic benefits of these proposals. The second reading outlines the moral and political case for taxing the ultra-wealthy, considering whether a steep tax on wealth could positively impact our democracy. Questions for discussion follow each reading.

Reading 1:

When the Rich Paid a Greater Share

A report published by Oxfam in 2019 showed that the richest 26 individuals in the world own as much wealth as the bottom half of humanity, some 3.8 billion people. This report is just the latest piece of evidence that wealth disparity across the world continues to grow.

A number of high-profile politicians have proposed that the wealthy should pay more in taxes. In early 2019, newly elected Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez caused a minor uproar in Washington, DC by proposing to nearly double the income tax rate on top earners. Under her plan, the rich would pay a tax rate of 70 percent on income over $10 million. Republicans roundly rejected this proposal, and even many Democrats dismissed it. New Jersey Democratic Representative Bill Pascrell dismissed a higher wealth tax as “comical.”

And yet, a Hill–HarrisX poll found that 59 percent of voters supported Ocasio-Cortez’s plan. Her proposal was popular in all regions of the country, including the more conservative South. Even 45 percent of self-identified Republicans approved.

Significantly increasing the tax rate on wealthy Americans is a policy idea with historical precedent. For most of the 20th century, the United States had much higher tax rates for the wealthy. In the 1930s, Presidents Hoover and Roosevelt both significantly increased taxes on the wealthy, and higher rates remained in place for decades. In a February 11, 2019, interview with Jeremy Hobson, host of radio station WBUR’s news show Here & Now, historian and journalist Rutger Bregman discussed the impact of this policy:

In the '50s and '60s, there was this period that historians call 'the golden age of capitalism.' This was the period when we had the highest rates of growth, the most innovation, when we put a man on the moon. And back then, during Eisenhower's presidency, for example, the top marginal tax rate in the U.S. was 91 percent, and the top estate tax was over 70 percent.

This can work perfectly well together with capitalism. It's really what you need if you want to tame capitalism, because by itself, capitalism is a very unstable system and you need these kind of laws and policies and institutions to stabilize it.

In spite of this track record, there has been a bipartisan drive since the 1970s to reduce tax rates for the wealthiest Americans. Today, there is a debate about whether raising taxes on top earners would have negative effects, possibly increasing tax evasion or making U.S. businesses less entrepreneurial. Alana Samuels, staff writer for The Atlantic, wrote about these in a 2016 article:

There are plenty of people who would argue that raising taxes may do more harm than good to the economy. If the rich are taxed more, they may become even more motivated to move their money offshore or to accounts where it can’t be tracked. That could mean less revenue for the government and government services in the end. And if the wealthy aren’t making, or keeping as much money—some say—the result could be a reduction in economic activity, with less capital available for entrepreneurship, leading to lower rates of business formation and fewer jobs. If true, that would be bad for the entire economy, especially low-wage earners.

But there is historical evidence that suggests these fears may not be more conjecture than actual threat. The U.S. economy is becoming less entrepreneurial over time, suggesting that the wealthy aren’t creating new businesses with all that extra money that used to go to taxes. And in the past, raising top tax rates hasn’t actually depressed economic activity or caused people to stash more money offshore.

Citing a paper by economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Stefanie Stantcheva, Samuels observes that countries such as the United States and Britain that reduced their tax rates since the 1970s saw inequality rise, while Denmark, which kept top tax rates high, experienced less inequality. She writes that among the 36 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), as tax rates on upper-income earners fell, the share of income accruing to the top 1 percent grew. Keeping tax rates high didn’t harm a country like Denmark’s GDP either, “suggesting that high taxes didn’t lead productive earners to flee, and low tax rates didn’t motivate them to produce more. According to the paper, while there isn’t a lot of proof that high taxes result in economic slack, there’s a compelling link between low taxation and a growth in inequality.”

A proposal like Representative Ocasio-Cortez’s to dramatically increase taxes on the wealthy may seem radical by today’s standards, but when compared to other periods in U.S. history, it appears to be a less dramatic proposition.

For Discussion

- How much of the material in this reading was new to you, and how much was already familiar? Do you have any questions about what you read?

- According to the reading, what were some of the economic impacts of higher tax rates on the wealthy in the United States in the decades after World War II?

- What are some possible negative consequences of raising the top income tax rate? How might you address a problem such as increased tax evasion?

- Do you think raising the top income tax rate be good or bad for lower-income people? Explain your position.

- A majority of Americans support increased taxes on the wealthy. What are some reasons that politicians might be hesitant to champion this issue or to support more dramatic proposals, such as Rep. Ocasio-Cortez’s?

Reading Two:

Can a Wealth Tax Help Reduce Inequality?

After Representative Ocasio-Cortez proposed an income tax of 70 percent on those making more than $10 million, Senator Elizabeth Warren, who is currently running for president, proposed taxing not just large incomes, but also accumulated wealth. Some estimates hold that a wealth tax on the richest 80,000 American households could bring in $2.75 trillion to the US government over ten years.

A lot of the arguments about greater taxes on the wealthy revolve around the idea that if the government had more tax revenues it could pay for popular programs such as Medicare for All or free college programs. However, there are also moral and ethical implications to the argument about taxing the wealthy that have little to do with raising revenue and a lot to do with our vision for what a good society might look like.

In an article for Jacobin in 2017, Roosevelt Institute fellow and research director Marshall Steinbaum argued that taxing the wealthy is fundamentally about redistributing power.

[Progressive taxation] was originally enacted to tame the excesses of wealth and power that dominated the economy in the Gilded Age. The point was not to raise money, nor even, really, to shift the burden of taxation towards those better able to shoulder it (though the latter played a role). Rather, it was to fundamentally alter the distribution of power in society.

When he took office in the depths of the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt and his Congressional allies increased the top marginal income tax rate from 25 percent to 63 percent, and a few years later to 79 percent. In 1936, only a single taxpayer earned enough to be subject to that rate: John D. Rockefeller Jr. The point was to make it de facto illegal to be too rich, to better ensure that economic well-being was broadly distributed throughout the economy and society.

When it’s illegal to be too rich, many of the things rich people do — exploit labor, monopolize markets, squeeze supply chains, offshore jobs, asset-strip their companies, commit fraud — aren’t worth doing, since the government takes the lion’s share of the proceeds. When marginal tax rates are high, every other stakeholder has a greater claim on the surplus from participating in a market economy.

Elizabeth Warren has proposed not just taxing income, but taxing wealth. While income is the money that people bring in in every year, wealth is the accumulated fortune that gets passed on from generation to generation. Wealthy people get most of their money from dividends and investment gains on money they already have, not from a monthly paycheck.

A wealth tax could be an important policy tool for combating inequality, but it would no doubt be a controversial one. John Cassidy, a staff writer for The New Yorker, wrote in a January 31, 2019 article about Warren’s proposed wealth tax:

Under Warren’s plan, the tax rate on wealth would be two percent, but it would only apply to American households worth at least fifty million dollars, of which there are fewer than eighty thousand. Fortunes of a billion dollars or more would be taxed at three percent….

Not everyone is thrilled about Warren’s proposal, of course. During a visit to New Hampshire, Mike Bloomberg, who [was] considering running for President in 2020, as a Democrat, claimed that Warren’s proposal was unconstitutional and brought up Venezuela…. On Capitol Hill, meanwhile, Mitch McConnell and two other Republican senators said that they would introduce a bill to repeal the federal estate tax, a type of wealth tax that has already been so weakened that it now hits fewer than two thousand families a year. So much for billionaires and Republicans.

But many moderate and progressive Democrats, far from recoiling from the Warren proposal, enthusiastically embraced it. “Wealth inequality in our nation is a national scandal,” Gene Sperling, a veteran Democratic policy wonk who served as a top economic adviser to Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, wrote on Twitter. “This type of wealth tax that @SenWarren is proposing is essential. It frees up dramatic amounts of resources that make it more likely the vast number Americans can have economic security & a shot at their own small nest egg.”

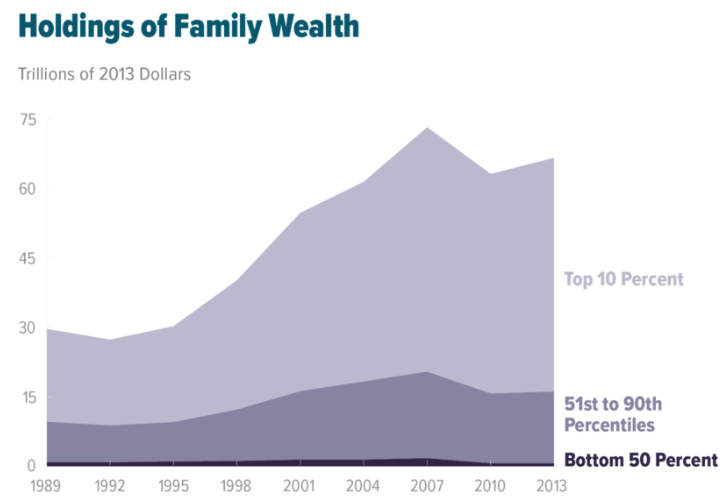

Since [1994] the share of income and wealth going to the top one percent, and especially the top 0.1 percent, has risen a good deal further, while the wages and incomes of regular American households have stagnated. Meanwhile, the Citizens United ruling, the rise of super pacs, and the lurch to the right of the Republican Party and, of course, the Trump Presidency have demonstrated the growing political power of the billionaire class, throwing into sharper relief [author Edward] Wolff’s point that “the current tax system in the United States leaves these vast differences in wealth and power largely untouched.” ...

In many policy circles, where taxing wealth is widely seen as an idea whose time has come, the debate is shifting to practicalities.

Three polls all found that a majority of Americans supported Warren’s wealth tax plan. Between 50 and 61 percent of people favored the plan, while only 20-23 percent opposed it. While a high percentage of Democrats favored the proposal, even among Republicans more people supported than opposed it.

Senator Warren’s push to tax not just income but wealth would represent a major shift in U.S. politics. Nevertheless, even having a discussion of the idea could help to prompt a meaningful conversation about wealth, inequality, and power in our political system.

For Discussion

- How much of the material in this reading was new to you, and how much was already familiar? Do you have any questions about what you read?

- What makes Senator Warren’s wealth tax proposal different from income tax proposals like that of Representative Ocasio-Cortez?

- Do you think that the growing gap between the rich and the poor in our society is a major problem? Why or why not? Should the government aim to reduce this gap?

- Economist Marshall Steinbaum makes the provocative proposal that it should be illegal to be a billionaire. What might be some of the reasons for such an argument? What do you think possible pros and cons of this idea might be?

- What are some reasons, other than raising money for government programs, that politicians might choose to implement a wealth tax? How does this connect to a vision of what our society should look like?

Research assistance provided by John Bergen.