On June 27, 2019 the U.S. Supreme Court, in Rucho v. Common Cause, announced a momentous decision: Federal courts have no power to police partisan gerrymandering. The high court overturned district court decisions in North Carolina and Maryland which held that state legislatures had engaged in extreme gerrymandering that had deprived citizens of their Constitutional rights.

In this lesson, students examine the abuse of the redistricting powers and consider why it has gotten worse, why it matters and the prospects for change without the intervention of federal courts.

Image: Steve Nass, Wikimedia Commons

Opening

Begin the activity by asking students if they know what gerrymandering. Give students the following multiple choice options.

Question: What is gerrymandering?

a. A procedure used in the Senate to end a filibuster

b. Negative, often personal, frequently inaccurate or exaggerated attacks on the opposition

c. Drawing the lines of political districts to help your own political party

d. Using the presidency (or other high office) to promote your ideas

e. The practice of smearing people with baseless accusations and investigations

f. Blocking a vote in the Senate by endless speech-making

g. It’s when a politician suggests an idea in public, and waits for the reaction before actually proposing it

Answer: c

Optional Question: All the multiple choices answers to the question above (including the wrong ones) are political terms. What are the terms described by items a through g above?

Answers:

a. cloture

b. mudslinging

c. gerrymandering

d. using the bully pulpit

e. McCarthyism

f. filibuster

g. a trial balloon

Student Reading 1:

How Gerrymandering Works

Every ten years, the federal government counts the population with the U.S. Census. State legislatures then use the census to redraw lines to get political districts that are (approximately) equal in population. It’s awfully tempting to take the opportunity of redistricting to advance one party or the other. When one party controls the legislature and the governorship, no compromise is necessary, and varying degrees of gerrymandering result.

Gerrymandering has enabled political parties to claim seats in Congress even when they represent a minority of voters. In 2016, Republicans took control of approximately 17 seats in Congress that they would not have won without gerrymandering, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at the NYU Law School.

Both Democrats and Republicans engage in gerrymandering, but the Republicans have seen much larger gains due to gerrymandering following the 2010 census.

Several factors led to more extreme gerrymandering after the 2010 Census:

- In a large number of states, one party controlled both houses of the legislature and the executive branch as well. Twenty of these “trifectas” were Republican and only eight were Democratic.

- Partisanship was on the rise in state and federal governments, and in the population as a whole

- Sophisticated computer calculations vastly improved the capability of political parties to locate and measure voting preferences by location.

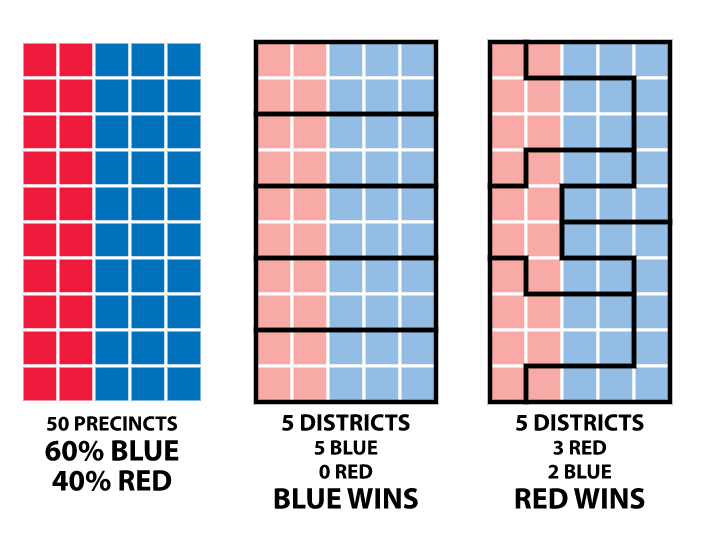

The ability to store and manipulate enormous quantities of information (aka “big data”) has facilitated the two main techniques of gerrymandering: “packing” and “cracking.”

Packing involves pushing large numbers of opposition voters into a single district. By gerrymandering in this way, you are giving your rival party one district where they are sure to win. But you are preventing them from having any significant impact in surrounding districts.

Cracking is the opposite. You spread the opposition’s voters over several districts, but not in sufficient numbers to challenge your own candidates.

Which tactic (or combination of tactics) a party will employ depends on the actual locations and concentrations of the districts being re-drawn. Technology has provided new levels of accuracy that allow gerrymanderers to maximize their party’s voting strength.

History

Gerrymandering is not new. Efforts to manipulate political lines date back to 1788. The word “gerrymander” itself was born in 1812, when Governor Gerry of Massachusetts who signed a law creating a district shaped like a salamander. Gerrymander is a portmanteau (the combining of two words to make a new one): gerry + mander. In 1812, the major parties were the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists, but the practice has continued to the current day with the Democratic and Republican Parties.

Sometimes district lines are redrawn to help (or hurt) a particular candidate, but the most controversial gerrymanders today are those whose purpose is to minimize representation of a party or racial group. Since the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Court has outlawed redistricting based primarily on race. However, charges of racial gerrymandering continue.

The Supreme Court has decided many cases involving gerrymandering. In its June 2019 decision, the Supreme Court majority argued that while “excessive partisanship in districting leads to results that reasonably seem unjust,” it is up to Congress and state legislative bodies (not the Supreme Court) to find ways to restrict it.

Student Quiz

Ask students:

1. Which of the following weird facts is in fact true?

a) Author Jerry Mander wrote a book titled “Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television” which ended being translated into eight languages.

b) The lines for the 2nd Congressional District in Michigan were drawn by the seven-year-old daughter of Sen. William Benner and submitted by accident.

c) According to Abraham Lincoln, “Had not the honorable Commonwealth of Virginia betrayed its long-held principles of democracy and yielded to the temptation of the gerrymander, the War Between the States could have been settled in the stateroom of a schooner.”

2. In drawing political districts to include just the right voters, legislators have come up with some very imaginatively shaped districts. Which of the following descriptions has been used to portray gerrymandered political districts?

a) Praying mantis

b) Goofy kicking Donald Duck

c) Upside-down elephant

d) Latin earmuffs

e) Bart Simpson fishing

f) Hanging claw

g) Pinwheel of death

h) All of the above

i) None of the above

(You might consider showing students images of gerrymandered districts: LINK

3. True or False

In the 5-4 Supreme Court decision that denied federal intervention in state gerrymandering, the five conservative justices formed the majority.

4. True or False

Prior to the 2018 election, a court in Pennsylvania declared the Republican gerrymandered redistricting illegal, and installed a nonpartisan redistricting plan. The state’s Congressional delegation went from 5 Democrats out of 18 seats to 9 out of 18 seats after the 2018 election.

Answers:

1) a

2) h

3) True

4) True

Student Reading 2:

Gerrymandering Impact & Solutions

Gerrymandering has led to to some major electoral “successes” by political parties that have won seats despite getting fewer votes overall.

North Carolina: In 2016 and 2018, Republicans won just over 50% of the statewide vote for legislative seats. Despite the close margin of victory, they were able—with districts they drew—to win 10 of the 13 races in both elections. Democrats won only 3 congressional seats despite getting 48% of the popular vote.

“I propose that we draw the maps to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and three Democrats, because I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and two Democrats.”

—Rep. David Lewis (R-NC, overseeing the redistricting process)

Wisconsin: In 2011, Republican state legislators redrew the district lines for the state assembly. In 2012, despite winning only 49% of the statewide vote, Republicans won 60 of the 99 seats available. In 2014, with 52% of the statewide vote, they won 63 assembly seats. In the 2018 elections, Republicans received only 46% of the votes for State Assembly, but won 64% of the races.

"[State legislators] will naturally choose the one that will give them an advantage at the ballot box. A little bit. Marginally."

—Robin Vos (co-chairman of the Republican Assembly Campaign Committee)

Maryland: After the 2010 Census, Democratic lawmakers redrew a district that had elected a Republican to Congress for 18 years. The new district added just enough Democratic-leaning communities to flip the district to Democratic in the following election.

“As a Maryland Democratic fundraiser told me: ‘Sure, gerrymandering stacks the deck (in elections). But it stacks in our favor.’”

—Baltimore Sun reporter Thomas Ferraro

“Indeed, it's not a stretch to say that most voters no longer choose their representatives; instead, representatives choose their voters.”

—Barack Obama

Possible Solutions

Americans oppose abusive redistricting by solid majorities. Polls show 70% favoring some controls over gerrymandering. Even among people with partisan affiliations, a majority disapprove of gerrymandering.

In Wisconsin—a state burdened with extreme gerrymandering—49 of the state’s 72 counties have passed resolutions opposing partisan redistricting. Democratic and Republican leaders (from Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama) have spoken out against the practice. Many good government organizations, such as the League of Women Voters and Common Cause, as well as the mainstream media, have called for reform.

Some 20 states have adopted measures to limit the power of legislatures to gerrymander. Most have created bipartisan or non-partisan commissions to conduct the redistricting or serve as advisory boards. Iowa uses a mathematical model that relies solely on demographics and excludes partisan information.

Other possible solutions include:

- Proportional representation. The number of legislators from each party is determined by the number of voters in the state identified with each party.

- Algorithm. Some propose developing mathematical formulas that will automatically determine district lines based not only on population, but on the compactness of an area and the shared interests in an area.

- Ranked choice voting. Instead of choosing only one candidate, voters in a large district would elect multiple representatives through ranked voting. (In ranked voting, voters indicate their first, second, and third preferences, for example, and candidates with the highest rankings win.)

What’s Next?

The Supreme Court decided that federal courts cannot fix partisan gerrymandering. Where does that leave the fight against unjust and unfair redistricting? The Court has left it up to either Congress or the individual states to fix the problem. Within states, that would mean state courts, state legislatures, or citizen initiatives (which are allowed in about half of the states).

There are reasons to be doubtful. Congress, in its current state of extreme partisanship, is unlikely to agree on a path to neutral redistricting. Meanwhile, within states, state legislators who have created districts that are hugely beneficial to their own party have celebrated the Supreme Court’s decision. States with party trifectas (with one party leading both houses of the legislature and the governorship) tend to have sympathetic courts as well.

That leaves the voter referendum. In the 2018 elections, voters in four states passed referenda calling for redistricting reforms. There are efforts in at least three more states to pass similar initiatives in the 2020 elections.

Questions for Discussion

- If most people in the country don’t like gerrymandering and would like changes to the redistricting process, why hasn’t the system been changed?

- Most of the world does not allow legislators to define their own political districts. Why do you think that is?

- Who should draw the lines, in your opinion – and why?

- What do you think of the alternate systems of voting described in the reading? Would they be preferable to our current system? Which system would you argue for, and why?

- If you were telling a younger sibling about the Supreme Court decision, how would you explain its importance?

Sources

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/what-the-supreme-courts-gerrymandering-decision-means-for-2020

https://www.brennancenter.org/blog/5-things-know-about-maryland-partisan-gerrymandering-case

https://www.baltimoresun.com/opinion/op-ed/bs-ed-gerrymandering-maryland-20150429-story.html