Gathering: What is Your Weather Today?

Invite students to use a weather word to share how they are doing. For instance, if they’re feeling angry, they might be a thunderstorm, a hurricane, or perhaps a smoldering heat wave. If they are feeling happy, they might be sunny day with not a cloud in the sky, or a cool, 60-degree, foggy day in fall.

Give students a moment to think, then send a talking piece around, as you invite them to share their weather one after the other. They can choose to explain and elaborate on their weather report, or not.

What Do These Names Have in Common?

Invite student to look at the following list of names

- Alex

- Bonnie

- Colin

- Danielle

- Earl

- Fiona

- Gaston

- Hermine

- Ian

- Julia

Based on this list of names and what you just shared about the topic of today’s lesson, ask students:

- What do you think today’s lesson might be about?

Elicit and explain that these are the named hurricanes of the 2022 season, so far. Today’s lesson will be about the weather, the environment, and environmental justice.

Word Web and Definition

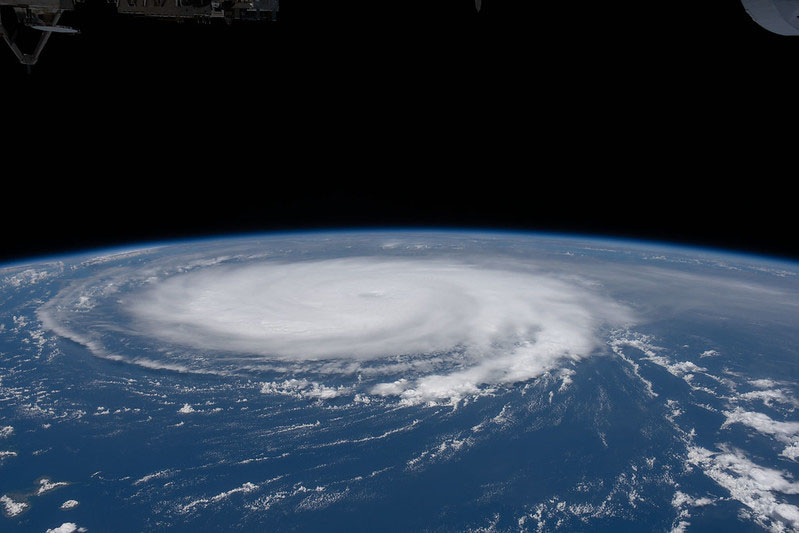

Invite students to share what they know about hurricanes.

Consider doing a word web: Write HURRICANE at the center of the board or sheet of chart paper. Then chart students’ associations with that word, writing the responses around the word “hurricane.” Then, draw lines from “hurricane” to the word associations, creating a word web.

When you have a full web and/or students’ word associations slow down, have students look over the web and invite a volunteer or two to share what they notice about the web:

- Are there any words that belong together in a group?

- Do you see any themes that have emerged from the group?

- Any surprises?

You might also consider having students share what feelings come up that they associate with the word hurricane.

Next, have a volunteer or two explain what a hurricane is.

Consider showing this 30-second clip from the National Ocean Service, What Is a Hurricane? to further round out students’ knowledge.

Pair Share: What’s In a Name?

The video we just watched mentions what is known as “hurricane season.” It tells us that hurricanes behave according to certain patterns – that there is a certain level of predictability about when and where they appear and potentially wreak havoc.

Ask students what they know about this “season” and about whether they have been tracking storms during this time frame.

Invite students in pairs to discuss this quote from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA):

“Storms are given short, distinctive names to avoid confusion and streamline communications.”

- What do you know about the names given to storms during hurricane season?

- How might giving storms short, distinctive names avoid confusion and streamline communication?

Back in the large group, invite some volunteers to share out what they discussed in their pairs using the questions to guide the conversation.

Class Discussion:

What’s in a Name?

Distribute Handout 1 below. Invite students to read the handout 1. They can either read it quietly for themselves, or ask four volunteers to each read a paragraph out loud for the class.

Having read the handout, ask students as a class to discuss:

- What sets a tropical storm apart from a hurricane?

- Why was the decision made to name tropical storms and hurricanes?

- Why do you think some names get reused in future hurricane seasons while other names are retired? (Think about storms like Hurricane Katrina which hit New Orleans and surrounding areas in 2015; Hurricane Sandy which hit New York City in 2012 and Hurricane Maria which hit Puerto Rico five years to the day that hurricane Ian hit the island this year).

Handout 1: Naming Hurricanes

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA):

“Until the early 1950s, tropical storms and hurricanes were tracked by year and the order in which they occurred during that year. Over time, it was learned that the use of short, easily remembered names in written as well as spoken communications is quicker and reduces confusion when two or more tropical storms occur at the same time. In the past, confusion and false rumors resulted when storm advisories broadcast from radio stations were mistaken for warnings concerning an entirely different storm located hundreds of miles away….

NOAA’s National Hurricane Center does not control the naming of tropical storms. Instead, there is a strict procedure established by the World Meteorological Organization. For Atlantic hurricanes, there is a list of male and female names which are used on a six-year rotation. The only time that there is a change is if a storm is so deadly or costly that the future use of its name on a different storm would be inappropriate. In the event that more than twenty-one named tropical cyclones occur in a season, a supplemental list of names are used.

Parade adds: “In 2022, there have already been nine named storms (which is about half of the predicted named storms for the year). And while each individual storm is unique, you may be surprised to find that the list of hurricane names gets made before the season even starts.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, any tropical storm that produces winds over 39 miles per hour gets a name. Those storms that reach winds over 74 miles per hour are then upgraded to hurricane status. So, although there have been eight other named storms so far this year, the first named hurricane that has actually hit the U.S., in Florida, is Hurricane Ian. ….

Small Group Discussion:

An Unusual Hurricane Season in 2022

Split your class into small groups of 3-4 students. Distribute Handout 2 below.

Invite students to either read the first paragraph of the handout silently in their small group, or ask a volunteer to read it out loud for the whole class to hear. Give small groups 6-8 minutes to discuss the questions below each paragraph, before reading (individually or together) the next paragraph in the handout, then discussing it in small groups. Continue this process for each of the four paragraphs.

Once the groups have finished their discussion of Handout 2, come back as a class and invite students to share some of the most important things that came up in their small group discussions about this handout. Consider using the questions in the handout to guide the conversation.

Handout 2: An Unusual Hurricane Season 2022

According to Scientific American:

“Hurricane activity in the Atlantic Ocean typically begins to ramp up in earnest around mid-August. But at that time this year, there wasn’t a storm to be seen anywhere across that vast stretch of ocean. Those quiet weeks capped off a nearly two-month lull that had forecasters scratching their head after initial predictions of a busy season. …. But by the end of September, it seemed like a switch was suddenly flipped. Four named storms formed within nine days, and two of them—Fiona and Ian—became destructive major hurricanes. The 2022 hurricane season’s 180-degree turn provides an object lesson in the competing influences that can either keep a lid on storm formation in the Atlantic or turn the region into what [hurricane researcher at Colorado State University] Klotzbach calls a “powder keg.”

Discuss:

- How do you feel about what you just read?

- How do you think communities vulnerable to tropical storms and hurricanes felt as the proverbial “switch was flipped”?

- What does Klotzbach say about hurricane seasons in general and this year’s hurricane season in particular?

- What do you think he means when he uses words like “predictions of a busy season,” “180 degree turn,” and “powder keg?” What does that language imply? How do you think that might impact communities vulnerable to tropical storms and hurricanes?

The Grid continues:

“Climate change is undoubtedly altering hurricanes and their traditional season in a number of ways that often combine to make the storms more damaging than in the past. But Klotzbach said this particular off-and-on season is more likely due to natural variability. Hurricanes are big, relatively infrequent events, and up or down years, or strangely clustered storms, don’t say much about the changing climate on their own.…. This year, specific conditions in August — in particular, strong wind shear, the change in wind direction and speed across varying altitudes — made it difficult for tropical storms to form. “In September, we’ve had much more conducive conditions, with shear running near to below average,” Klotzbach said. “Midlevel moisture has also increased somewhat, allowing for conditions where hurricanes can develop and thrive.”

Discuss:

- How do you feel about what you just read?

- How do you think communities vulnerable to tropical storms and hurricanes are feeling about what Klotzbach is saying?

- What does Klotzbach say about hurricane seasons in general and how that relates to this year’s hurricane season in particular?

- What do you think he means when using words like “off-and-on season,” and “natural variability?”

Adds the New England Journal of Medicine:

“Climate change has been linked to changes in Atlantic hurricane behavior, making storms more destructive to the built environment and vital infrastructure, more harmful to the physical and mental health of island-based and coastal populations, and more deadly in their aftermath. These escalating effects … represent a double environmental injustice:

[1.] socioeconomically disadvantaged and marginalized populations sustain disproportionate harm and loss, with more hazardous storms [worsening] inequity; and

[2.] while the populations most vulnerable to Atlantic hurricanes, especially those in small-island states, contribute virtually nothing to climate change, they are among those most exposed to risks that are worsened by the carbon emissions from higher-income countries [and communities].”

Discuss:

- How do you feel about what you just read?

- How do you think communities vulnerable to tropical storms and hurricanes feel about climate change and the implications of that on their communities?

- What does The New England Journal of Medicine say about climate change and changes in Atlantic hurricane behavior?

- What do you think the term “environmental injustice” mean?

- What is the double environmental injustice that is outlined in this paragraph?

The North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) adds:

“On September 20, 2022, many people in Puerto Rico experienced the five-year anniversary of Hurricane María without electricity and running water. Fiona, a category 1 hurricane, dealt yet another devastating blow to the archipelago’s centralized energy system, which relies on imported fossil fuels. When Fiona made landfall on September 18, only households and businesses with rooftop solar or generators were able to keep the power on. The dangerous storm damaged and destroyed roads, bridges, and water infrastructure, downed electric transmission and distribution lines, caused landslides, and flooded entire neighborhoods, leaving many without safe and healthy living conditions.”

Discuss:

- How do you feel about what you just read?

- How do you think the people of Puerto Rico feel right now?

- What does The North American Congress on Latin America say about the five-year anniversary of Hurricane Maria? How did Fiona make things even worse?

- What does the paragraph say about fossil fuels versus solar energy?

- Who do you think might have access to back up generators and/or solar panels on their roofs. Who relies on the government energy grid?

- How does that relate to environmental injustice even on the island of Puerto Rico itself?

Class Discussion:

Voices on Puerto Rican Climate Injustice & Possible Next Steps

Distribute Handout 3 below.

Invite volunteers, one after the other, to read the quotes in the handout out loud for the whole class to hear or have students quietly read the quotes to themselves.

Once students have heard or read the quotes, ask them some or all of the following questions:

- Which quote most resonates with you? Why?

- What did you learn from the quotes about the challenges faced by Puerto Ricans?

- What did the quotes tell you about how Puerto Ricans are impacted by environmental crises?

- Are the environmental challenges faced by Puerto Ricans all “natural” crises? Is there a human-made component as well?

- What are some of the ways these challenges might be addressed, according to these quotes?

- How do you feel about the possible strategies or steps suggested in these quotes?

- How does what we discussed today relate to other environmental challenges that you know about in the U.S. and abroad?

Handout 3: Voices on Puerto Rican Climate Injustice & Possible Next Steps

Puerto Rican Voices:

“After Hurricane Maria, it became very clear that the future of the electric system here in Puerto Rico is a matter of life and death.” (Ruth Santiago, Community and Environmental Activist)

“Hurricane Fiona is just one more example of the urgency needed to transition to an electrical system that’s resilient and provides people what they need, which is rooftop solar and storage” …. “Puerto Rico needs something that’s not going to go out every time a major storm hits, because we’re just getting more and more of [these intense storms]….” (Cathy Kunkel, energy program manager at San Juan-based sustainability nonprofit Cambio PR)

“I wanted to offer communities the possibility of enjoying sustainable and renewable energy .… Energy independence is essential for people if there is another emergency.” (Ada Ramona Miranda, who helps local community organizers install solar roofs on homes and businesses so they don’t have to rely on the expensive, fragile electrical grid)

“Community and civil society groups should be part of the decision-making processes to ensure that the electric system serves the public interest and prioritizes more resilient options such as rooftop solar and storage, coupled with energy efficiency and other alternatives to centralized fossil fuel generation.” (Ruth Santiago, Community and Environmental Activist)

The [power] plant—long owned by the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), a government agency—held the promise of jobs and economic prosperity for the region. But the assurances the government made long ago, … contrast sharply with the current reality of empty(ing) neighborhoods due to out-migration, mass unemployment, and poverty. There is no end in sight to the disproportionate contamination and pollution that residents seem condemned to endure. (Carmen, a 61-year-old grandmother whose family worked as sugar cane cutters in the area where the island’s power plant was built in the early 1970s)

“We have a right to live in a clean environment … Or it is because we are poor that we have to get used to being sick as a result of industrial contamination in our communities? Do we not have the same human rights as the wealthy and white people in this country?” (Carmen, a 61-year-old grandmother, whose family worked as sugar cane cutters in the area where the island’s power plant was built in the early 1970s)

“In the struggle over coal ash disposal, poor and mostly Black communities in Puerto Rico’s hinterlands are being forced to sacrifice their health, and the health of their environment, to support the island’s energy-intensive economy and lifestyle …. The crisis illustrates two closely connected problems: environmental injustice and environmental racism.’’ (Anthropology Professor and native of Puerto Rico, Hilda Lloréns)

“There have been quite a few power outages since [Hurricane Maria in 2017] and so the community center has been able to provide sort of an oasis of light [because it converted its energy source to rooftop solar panels and a battery energy storage system] … It's a very low-income community that is disproportionately impacted by the big power plants.” (Ruth Santiago, Community and Environmental Activist)

“As a native of the island’s southeast, I have been following these developments closely. Historically this region has been a zone of human exploitation and natural resource extraction. In the struggle over coal ash disposal, poor and mostly black communities in Puerto Rico’s hinterlands are being forced to sacrifice their health and the health of their environment to support the island’s energy-intensive economy and lifestyle. (Anthropology Professor and native of Puerto Rico, Hilda Lloréns)

“We are hearing about environmental injustices that have been happening for decades that we need to resolve urgently …. And now we have the resources and the will to begin to address some of these concerns." (Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan visiting the island after Hurricane Fiona)

"We hope we will finally be heard … I do not want to leave my grandchildren with a community that is getting worse." (Wanda Figueroa, a resident of the Cataño community in San Juan, detailing her family’s exposure to sewage runoff.)

"We have had bad experiences with the money we were supposed to receive to rebuild after Maria. Our people don't believe the promises that are made.” (Wendymar Deliz, secretary of the community emergency response group PASE)

“The source of the coal ash is a 454-megawatt, coal-fired electric power plant on the southern part of the island in the Guayama-Salinas region. More than half of the area’s residents live below the poverty line, and many identify as Black ….. Most residents rely on fishing to make a living—an industry that is now in jeopardy from the coal ash.” (Anthropology Professor and native of Puerto Rico, Hilda Lloréns)

"To make renewable energy projects accessible to a large swath of vulnerable and low resourced communities, stakeholders need to each understand their particular role to accelerate the development of these projects. Government and NGOs … should take on the role of … mak[ing] the total project cost accessible for communities with scant organic resources." (C.P. Smith, Executive Director, of Cooperativa Hidroeléctrica de la Montaña -Puerto Rico's first electric power cooperative)

“When a storm comes and the power goes out, first responders are in saving mode. It’s not their role to figure out the power situation,” … [I hope] to continue distributing solar power roofs and battery storage to the remaining 77 fire stations on the island.” (Hunter Johansson, founder of the non-profit Solar Responders, working to install solar panels in fire stations on the island to ensure first responders are able to continue their work when the electric grid fails)

With infrastructure that was already vulnerable, “it’s absolutely imperative that FEMA not fund rebuilding an inadequate system. [Improving the island’s grid would entail] massive new investments in wind, solar, geothermal, and other clean energy sources. Puerto Rico’s year-round sun makes solar an appealing option.” (Judith Enck, former Environmental Protection Agency administrator for Region 2, which includes Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands)

American Voices

“Once the more immediate crisis has been alleviated, Puerto Rico will stare down the daunting task of rebuilding and reimagining what [its] … defenses should look like. And that should be an opportunity for a complete reimagining of Puerto Rico’s energy system, which uses some of the least sustainable fuels at some of the highest costs in the U.S. ….Relying on a single power plant prone to flooding is an unsustainable model.… Microgrids [are] one solution: When a part of the infrastructure goes down, the other ones keep working.” (Otis Rolley, the 100 Resilient Cities regional director for North America)

“Energy is a lifeline for the people of Puerto Rico to access clean water, food and health services. Yet … years after Maria, work to rebuild the electric system has barely begun and blackouts are commonplace. Rural communities remain the hardest hit (Sierra Club President Ramón Cruz and Environmental Defense Fund President Fred Krupp)

“Complicating matters is the premium Puerto Ricans pay for energy that is both dirty and unreliable because of an outdated, centralized power infrastructure. Most electricity is generated from old oil-burning power plants fed by expensive imports, then transported by a fragile, decrepit delivery system. The poor design, with heavy reliance on fossil fuels, adds to high electricity costs and air pollution that harms people’s health.” (Sierra Club President Ramón Cruz and Environmental Defense Fund President Fred Krupp)

“Clean energy and community leadership are key to a system that will protect the island from the next storm and improve the lives of all Puerto Ricans.” (Sierra Club President Ramón Cruz and Environmental Defense Fund President Fred Krupp)

“The surest path to lowering rates and stabilizing the finances of the electrical system is to end Puerto Rico’s dependence on fossil fuels .… The numbers speak for themselves …. To combat this environmental injustice and make solar accessible to everyone, money from Puerto Rico’s $13 billion post-Maria federal recovery aid needs to be allocated to create centralized and distributed solar energy, instead of centralized natural gas and diesel plants …. Creating institutional incentives for low-income families like grants or federal tax credits could help.” (Tom Sanzillo, director of financial analysis for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis)

“Regardless of what work you do ahead of time, no one can be completely ready for a Category 5 hurricane. But a more resilient grid could help the region be far more prepared to weather one.” (Otis Rolley, the 100 Resilient Cities regional director for North America)

Closing

What is one wish you have for Puerto Ricans going forward?

Additional Reading on Climate Justice

NACLA: Another Hurricane Makes Clear the Urgent Need for Rooftop Solar in Puerto Rico

Explanation of why we’re getting some of these major storms now: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-hurricane-season-went-from-quiet-to-a-powder-keg/

Hurricane News:

Hundreds of thousands of people have been left without power, after Storm Fiona hit Canada's coastline. Fiona was downgraded from a hurricane to a tropical storm on Friday. But parts of three provinces experienced torrential rain and winds of up to 160km/h (99mph), with trees and powerlines felled and houses washed into the sea. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the situation was critical, and promised to provide support through the army.

A hurricane warning … is now in effect for the entire coastline of South Carolina. "If you haven't yet made plans for every contingency, this afternoon is the time to do so," Gov. Henry McMaster said on Thursday. The new round of warnings for the Atlantic Coast comes as residents and emergency crews on the western side of the Florida peninsula take stock of the immense damage done by Ian's massive storm surge and high winds. "Widespread, life-threatening catastrophic flash and urban flooding, with major to record flooding along rivers, will continue across central Florida," the hurricane center said.