To the Teacher:

2018 is the 50th anniversary of a landmark protest at the Miss America beauty pageant. The protest was part of a new period of feminist activism—one with renewed significance in the #MeToo era.

This lesson consists of three readings that introduce students to the history and significance of the Miss America protest, placing it in the context of the era’s wider women’s liberation movement. The first reading describes the protest itself and the motivations of participants. In the second, students engage directly with a primary source document—a 1968 press release in which protest organizers explain their objections to the beauty contest. The third reading describes the larger context of the era’s feminist movement and discusses how that movement’s accomplishments affect us today. Questions for discussion follow each reading.

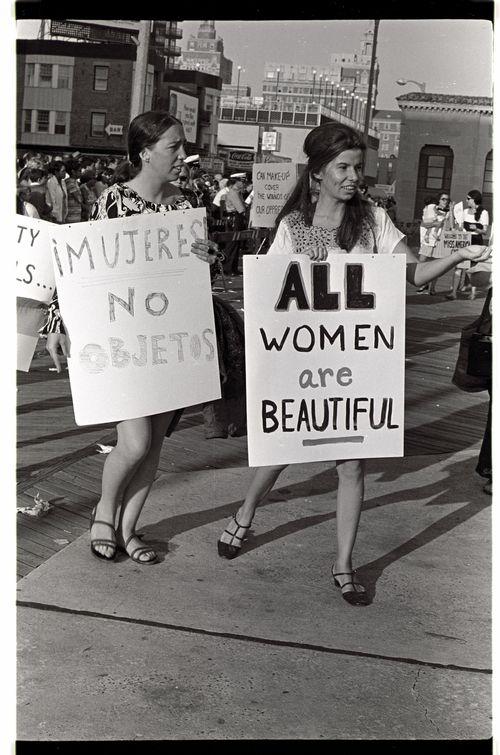

Miss America Protest, September 7, 1968. Photo by Bev Grant. See more photos of the protest here.

Reading One: Remembering the 1968 Miss America Protest

2018 is the 50th anniversary of a landmark protest at the Miss America beauty pageant. The protest signaled the arrival of a new period of feminist activism—one with renewed significance in the #MeToo era.

On September 7, 1968, more than a hundred women marched on the boardwalk in Atlantic City, NJ, near where the beauty pageant was being held. They threw beauty products and women's magazines into a "freedom trashcan," and crowned a live sheep Miss America. Others bought tickets to infiltrate the hall, unfurling a banner and disrupting the pageant.

In the 1960s, the Miss American pageant was a major televised event. “Everybody tuned into Miss America back then—this was like the Oscars,” explained one of the protest participants, Alix Kates Shulman. Making national headlines, the protest thrust the emerging women’s liberation movement into the national spotlight. Writer and professor Roxane Gay described the demonstration in a January 2018 article in Smithsonian magazine:

On August 22, the New York Radical Women issued a press release inviting “women of every political persuasion” to the Atlantic City boardwalk on September 7, the day of the contest. They would “protest the image of Miss America, an image that oppresses women in every area in which it purports to represent us.” The protest would feature a “freedom trash can” into which women could throw away all the physical manifestations of women’s oppression, such as “bras, girdles, curlers, false eyelashes, wigs, and representative issues of Cosmopolitan, Ladies’ Home Journal, Family Circle, etc.” The organizers also proposed a concurrent boycott of companies whose products were used in or sponsored the pageant. Male reporters would not be allowed to interview protesters, which remains one of the loveliest details of the protest….

The organizers obtained a permit, detailing their plans for the protest, including barring men from participating, and on the afternoon of September 7, a few hundred women marched on the Atlantic City boardwalk, just outside the convention center where the pageant took place. Protesters held signs with such statements as “All Women Are Beautiful,” “Cattle parades are demeaning to human beings,” “Don’t be a play boy accessory,” “Can make-up hide the wounds of our oppression?”The protesters adopted guerrilla theater tactics, too. One woman performed a skit, holding her child and pots and pans, mopping the boardwalk to exemplify how a woman’s work is never done. A prominent black feminist activist and lawyer, Florynce Kennedy, who went by Flo, chained herself to a puppet of Miss America “to highlight the ways women were enslaved by beauty standards.” Robin Morgan, also a protest organizer, later quoted Kennedy as comparing that summer’s violent protests at the Democratic National Convention to throwing a brick through a window. “The Atlantic City action,” Kennedy continued, “is comparable to peeing on an expensive rug at a polite cocktail party. The Man never expects the second kind of protest, and very often that’s the one that really gets him uptight.”

The freedom trash can was a prominent feature, and the commentary about its role in the protest gave rise to one of the great misrepresentations of women’s liberation—the myth of ceremonial bra-burning. It was a compelling image…. But it never actually happened. In fact, officials asked the women not to set the can on fire because the wooden boardwalk was quite flammable.

The 1968 protest connected the oppression of women with many other forms of injustice, including racism. As historian Paige Welch explained in a September 9, 2016 article in The Conversation:

Many now hail [the protest] as the opening salvo of the second-wave feminist movement in America. Less well known is that they saw the pageant as the nexus of many problems with American society: racism, war, capitalism and even ageism. The organizers had roots in radical leftist causes, including the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements.

Upon descending on Atlantic City, women’s liberation protesters distributed a leaflet that proclaimed “No More Miss America!” In it they denounced the pageant as “Racism with Roses,” a pointed critique of an event that put white women on a pedestal while ignoring African-American, Latina and Native American women.

After the event, protest organizers celebrated their success, but they also offered self-criticism. In a 1968 essay, organizer Carol Hanisch noted, “We didn't say clearly enough that we women are FORCED to play the Miss America role—not by beautiful women, but by men we have to act that way for and by a system that has so well institutionalized male supremacy for its own ends.”

Nevertheless, the organizers were clear that their protest made an important impact. Later writing in The Feminist Memoir Project, Hanisch explained:

When we read the morning papers, we knew our immediate goal had been accomplished: alongside the headline of a new Miss America being crowned was the news that a Women’s Liberation Movement was afoot in the land and that it was going to demand a whole lot more than “equal pay for equal work.” We were deluged with letters, more than our small group could possibly answer, many passionately saying, “I’ve been waiting all my life for something like this to come along.” Taking the women’s liberation movement into the public consciousness gave some women the nudge they needed to form their own groups. They no longer felt so alone and Isolated.

In subsequent years, the feminist movement scored a string of political and social victories that would change the way that Americans of all genders think about themselves and their society.

For Discussion:

- How much of the material in this reading was new to you, and how much was already familiar? Do you have any questions about what you read?

- According to the reading why did the women involved want to protest the Miss America pageant?

- Why do you think the Miss America protest was effective at drawing attention to the cause of women’s rights?

- What do you think of the tactics the protesters used? Why do you think they used them?

- According to the readings, the protesters cited some limitations to their action. What were their own criticisms? What do you make of these?

- The protesters made considerable efforts to address political questions beyond gender discrimination. Why do you think they saw these other issues as connected? Do you agree with them that the issues are connected? Why or why not?

Reading Two: No More Miss America! A Primary Source Document

The following document contains excerpts from a press release written and released by the New York Radical Women in advance of their protest. The purpose of the press release was to communicate the reason for their demonstration and to attract the interest of the media. Consider what it might have been like to read—and write—such a document in 1968, as well as the impression it makes today:

NO MORE MISS AMERICA!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

On September 7th in Atlantic City, the Annual Miss America Pageant will again crown "your ideal." But this year, reality will liberate the contest auction-block in the guise of "genyooine" de-plasticized, breathing women. Women's Liberation Groups, black women, high-school and college women, women’s peace groups, women's welfare and social-work groups, women's job-equality groups, pro-birth control and pro-abortion groups—women of every political persuasion—all are invited to join us in a day-long boardwalk-theater event, starting at 1:00 p.m. on the Boardwalk in front of Atlantic City's Convention Hall. We will protest the image of Miss America, an image that oppresses women in every area in which it purports to represent us. There will be: Picket Lines; Guerrilla Theater; Leafleting; Lobbying Visits to the contestants urging our sisters to reject the Pageant Farce and join us; a huge Freedom Trash Can (into which we will throw bras, girdles, curlers, false eyelashes, wigs, and representative issues of Cosmopolitan, Ladies' Home Journal, Family Circle, etc.—bring any such woman-garbage you have around the house); we will also announce a Boycott of all those commercial products related to the Pageant, and the day will end with a Women's Liberation rally at midnight when Miss America is crowned on live television… It should be a groovy day on the Boardwalk in the sun with our sisters. In case of arrests, however, we plan to reject all male authority and demand to be busted by policewomen only. (In Atlantic City, women cops are not permitted to make arrests—dig that!)

Male chauvinist-reactionaries on this issue had best stay away, nor are male liberals welcome in the demonstrations. But sympathetic men can donate money as well as cars and drivers. We need cars to transport people to New Jersey and back.

Male reporters will be refused interviews. We reject patronizing reportage. Only newswomen will be recognized….

We Protest:

—The Degrading Mindless-Boob-Girlie Symbol. The Pageant contestants epitomize the roles we are all forced to play as women. The parade down the runway blares the metaphor of the 4-H Club county fair, where the nervous animals are judged for teeth, fleece, etc., and where the best "Specimen" gets the blue ribbon. So are women in our society forced daily to compete for male approval, enslaved by ludicrous "beauty" standards we ourselves are conditioned to take seriously.

—Racism with Roses. Since its inception in 1921, the Pageant has not had one Black finalist, and this has not been for a lack of test-case contestants. There has never been a Puerto Rican, Alaskan, Hawaiian, or Mexican-American winner. Nor has there ever been a true Miss America—an American Indian.

—Miss America as Military Death Mascot. The highlight of her reign each year is a cheerleader-tour of American troops abroad—last year she went to Vietnam to pep-talk our husbands, fathers, sons and boyfriends into dying and killing with a better spirit. She personifies the "unstained patriotic American womanhood our boys are fighting for."... We refuse to be used as Mascots for Murder.

—The Consumer Con-Game. Miss America is a walking commercial for the Pageant's sponsors. Wind her up and she plugs your product on promotion tours and TV—all in an "honest, objective" endorsement. What a shill….

—The Irrelevant Crown on the Throne of Mediocrity. Miss America represents what women are supposed to be: inoffensive, bland, apolitical. If you are tall, short, over or under what weight The Man prescribes you should be, forget it. Personality, articulateness, intelligence, and commitment—unwise. Conformity is the key to the crown—and, by extension, to success in our Society….

NO MORE MISS AMERICA!

For Discussion:

- How does the language used by protesters 50 years ago appear now? Are there particular words or phrases that are new to you? Are there portions of the press release that might have been clear in 1968 that seem confusing today?

- What are some of the objections that the protesters make to the pageant? Do any in particular stand out for you?

- The authors of the press release note that they will only speak to women reporters. Why do you think this was the case? Was this a good idea? What do you think the impact of this decision might have been?

- The press release was intended to answer basic questions that one might have about the protest. Did it answer questions you had? What might you still want to know?

- To what extent have the protesters' demands been met today? Which challenges still remain?

Reading Three: The Impact of the Women’s Liberation Movement

The Miss America protest was a part of a wider social movement. Although it was important in generating public awareness about a new wave of feminist action, it did not take place in a vacuum. Rather, it was part of and helped to fuel a much wider array of organizing, protests, and legal action. And this action had significant consequences. Over the course of just a few decades, feminists scored a string of important political victories. Professors Linda Gordon and Rosalyn Baxandall recounted the successes of the women’s liberation movement in a June 15, 2000 article in The Nation:

The movement’s impact cannot be easily encapsulated. Its judicial and legislative victories include the legalization of abortion in 1973, federal guidelines against coercive sterilization, rape-shield laws that encourage more women to prosecute their attackers, affirmative action programs that aim to correct past discrimination—although not the Equal Rights Amendment, which failed in 1982, just three states short of the required two-thirds.

But the most salient accomplishments occurred not in law but in the economy and the society, involving an accumulation of changes in the way people live, dress, dream of their future and make a living. Feminists turned violence against women, previously a well-kept secret, into a public political issue; made rape, incest, battering and sexual harassment understood as crimes; and got public funding for shelters for battered women.

Because of feminist pressure, changes in education have been substantial: Curriculums and textbooks have been rewritten to promote equal opportunity for girls, in the universities and professional schools more women are admitted and funded, and a new and rich feminist scholarship has, in some disciplines, overcome opposition and won recognition. Title IX, passed in 1972 to mandate equal access to educational programs, has worked a virtual revolution in sports.

As regards health, for example, many physicians and hospitals have made major improvements in the treatment of women; about 50 percent of medical students are women; women successfully fought their exclusion from medical research; and diseases affecting women, such as breast cancer, now receive better funding thanks to women’s efforts. In supporting families, feminists organized daycare centers, demanded daycare funding from government and private employers, developed standards and curriculums for early childhood education, fought for the rights of mothers and for a decent welfare system.

Feminists have also struggled for better employment conditions for women. They won greater access to traditionally male occupations, from construction to the professions and business. They entered and changed the unions and have been successful at organizing previously nonunion workers such as secretaries, waitresses, hospital workers and flight attendants. As the great majority of American women increasingly need to work for wages throughout their lives, the feminist movement tried to educate men to share in housework and childrearing. Although women still do the bulk of the housework and childrearing, it is also commonplace today to see men in the playgrounds, the supermarkets, PTA meetings.

Alongside these changes, there has been a more fundamental shift in the way that people think about gender divisions in our society. In fact, the very success of the movement in establishing a new “normal” has made it hard to appreciate the magnitude of the change in consciousness that has taken place over a relatively brief period of time. Journalist Ellen Willis recalled this transformation:

Any woman who says that radical feminism has made no difference in women’s lives either is too young to have lived through the pre-feminist years, or has thoroughly repressed them. I lived through them, and remember all too well. I remember a kind of blatant, taken for granted, un-self-conscious sexism that no one could get away with today pervading every aspect of life. I remember, as a Barnard student, wanting to take a course at Columbia and being told to my face that the professor didn’t want “girls” in his class because they weren’t serious enough. I remember, as a young journalist, being asked by an editor to use only my first initial in my byline because the magazine had too many women writers.

I remember having to wear uncomfortable clothes, girdles and stiff bras and high heels. I remember being afraid to have sex because I might get pregnant, and too tense to enjoy it because I might get pregnant. I remember the panic of a late period. I remember when a friend of a friend came to New York for an illegal abortion, remember us trying to decide whether her pain and fever were bad enough to warrant going to the hospital and then worrying that we’d waited too long, remember her fear of admitting what was wrong, and the doctor yelling at her for “going to a quack” and refusing to reassure her that she would live.

I remember that I was supposed to feel flattered when men hassled me on the street, and be polite and tactful when my dates wouldn’t take no for an answer, and have a “good reason” for refusing. I remember, too, feeling pleased to be different from other women—better—because I was ambitious and contemptuous of domesticity and “thought like man,” while at the same time, in my personal and sexual relationships with men, I was constantly being reminded that I was after all “only a woman”; I remember the peculiar alienation that comes of having one’s self-respect be contingent on self-hatred.

But such particulars only begin to describe the profound difference between a society in which sexism is the natural order, whether one likes it or not, and one in which sexism is a problem, the subject of debate, something that can be changed.

As the recent #MeToo movement has shown, sexism, harassment, and sexual violence persist as major social challenges. But the bold movements and strategies of the past did bring about significant changes, and that history is worth reflecting on.

For Discussion

- How much of the material in this reading was new to you, and how much was already familiar? Do you have any questions about what you read?

- This reading discusses many of the changes made by the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 70s. What are some examples it cites? Does any change strike you as particularly important?

- What do you think the world would be like today without the feminist movement? How do you think your life might be different?

- Do you think that these changes would have taken place if actions such as the Miss America protest had not happened? How might the one protest have contributed to wider efforts by the movement?

- While Gordon and Baxandall point out some of the many gains achieved by the women's movement, today's feminists say much remains to be done. The #MeToo movement has highlighted the prevalence of sexual harassment and assault. The U.S. still does not provide everyone with universal childcare. What do you think women and their allies need to be fighting for today?

- Journalist Ellen Willis argues that the most profound impact the movement made was in moving from “a society in which sexism is the natural order, whether one likes it or not, and one in which sexism is a problem, the subject of debate, something that can be changed.” What do you think of this statement? How is it relevant today, given the problems that still remain?

—Research assistance provided by John Hess.